30 Seconds of Beckettian Inspiration

A Runtime Analysis of Samuel Beckett's "Breath"

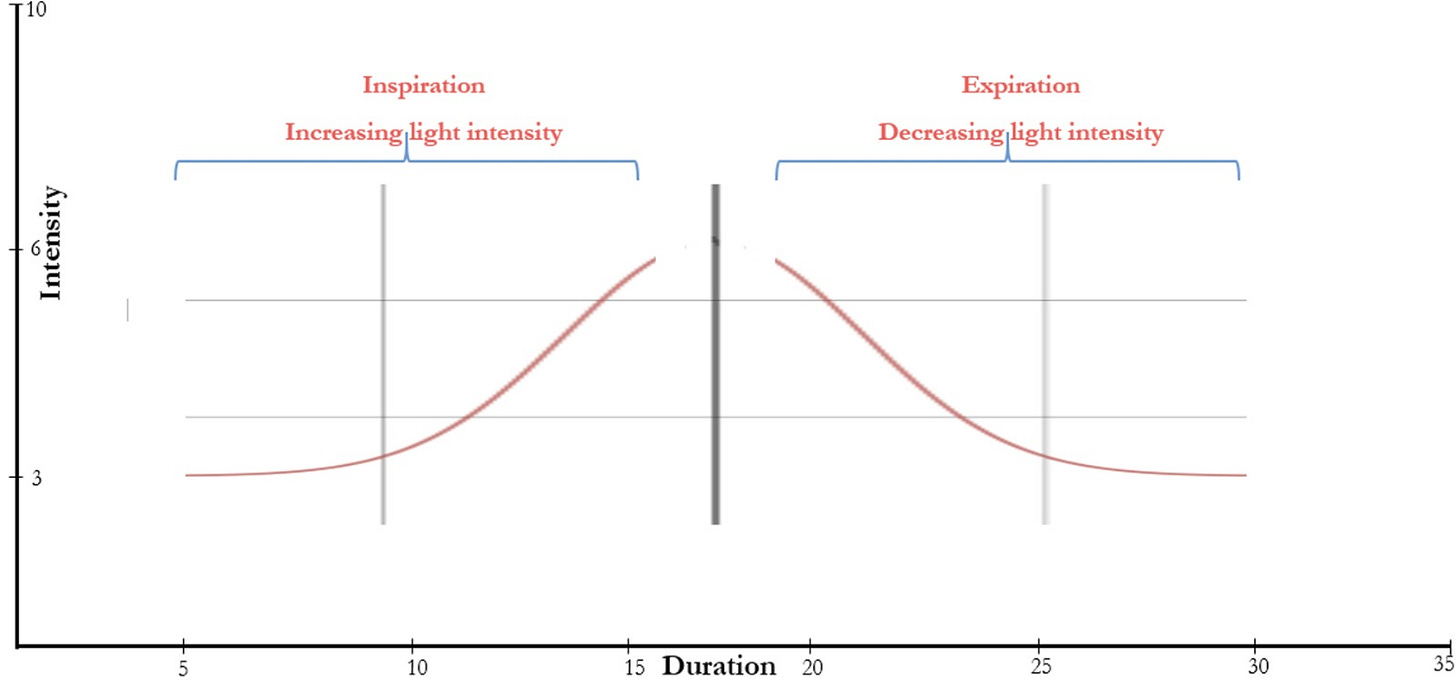

Breath, Beckett’s short piece first performed in 1969, literally stages one cycle of the act of breathing as it is performed by an unseen individual. Background lighting of low intensity illuminates this respiratory event, and both effects begin and terminate with a cry. After the first cry, the low light modulates its intensity in tandem with the breath for the duration of one wave. At the center of this wave—after inspiration and prior to expiration—hangs a five-second interlude of silence. Finally, a cry identical to the one that preceded the breathing completes the performance. In total, it lasts approximately 30 seconds

As a dramatic construct, Breath proposes a diegetic characterization of space and time as well as a logic of conversion between various spatiotemporalities. The text behaves rather like an experiment into the nature of space, as it issues electrons and sonar probes into the environment to investigate and highlight its nature. These ephemera of the performance, while perhaps not constitutive of the space, are so much one with their context that any change in the plot elicits a transformation of the entire space. The rubbish scattered about the stage symbolizes the incidental and almost irrelevant nature of the performance’s material aspects, as these desultory objects exist solely as a foil to the immaterialities that constitute the narrative. The characters that matter are the immaterial light, sound, and breath, and their activities unfold intensively, as opposed to the quality of extension associated with matter.

The narrative, thus concerned with the form rather than the content of the space, conspicuously avoids the physical characteristics of the human players whose presence it nevertheless suggests, opting instead to highlight ephemera that are of necessity perceived obliquely—light “seen” by the level of visibility it grants its scattered objects; air perceived by the audibility of motion precipitated by a breather who remains materially in absentia.

The narrative distils from matter properties that support conversion between its featured spatiotemporalities. In mathematics, sound (cry and breath) and light receive formal treatment as waves, and Beckett, by presenting them as such—standing waves of inspiration and expiration, of increasing and diminishing visibility—reduces traditionally material and embodied activities to terms that effectively underscore their morphological commonalities. This phrase is meant in a more etymologically faithful sense than is usually the case: that is, I see morphological commonalities as similarities based on the logic or form of the materialities in question.

The mind, as agent of logic and form, is ineluctably drawn into the performance by being that mechanism capable of transforming the narrative arc of an instance of respiration into a Gaussian or bell curve. It does so by extracting from each that similar form (the said curve), which functions as the principle of conversion between narrative and breath. The mind, in short, apprehends the isomorphism Beckett perceived: that which prompted his metonymic representation of a character’s entire life by a breath and the reduction of its vicissitudes to respiratory oscillations. And it is this same abstraction which motivates my discussion of Beckett’s (already formal) narrative in the language of time, space, and modulation.

Several aspects of these ephemera motivate this response: (1) the ascent of inspiration as it measures abstract spatiotemporal qualities such as volume (lung capacity) while the flow increases to its maximum; (2) the modulation of sound as it measures the progress or displacement of air through space; and (3) the change in the light’s intensity as it negotiates with shadow to highlight the elasticity of the respiratory cocoon into which the text transforms the proscenium.

The image above, as a formalization of Beckett’s condensed diegetic, tracks the distension of space in a graph that meanders its way to a temporary respite, at which ensues an electromagnetic stasis mingled with a silence to be held for “about five seconds” (211). Beyond this halfway point, the quality of the narrative alters: as it seeks a resolution of the climax and heads toward a denouement, the arc adopts a concavity that inverts the trace of its progress thus far. This inversion aptly represents the activities of the second half of the play, in which Beckett simply reverses the order and direction of the previous actions.

Breath’s superimposition of an instance of respiration upon the narrative arc to construct space in diegetic form motivates this project’s approach to narrative from a perspective of the mathematical disciplines that study spaces. A topology is an abstract structure that enumerates the basic qualities necessary to the definition of a space of open sets. As a collection of smaller sets, it imposes a rule of closure upon its elements (sets) that ensures the continued inclusion within itself of any union of those subsets or of any finite intersection of their elements. These, along with the added condition that the null and original sets also be considered elements, represent the entire set of axioms that constitute a fully functional topology.

Topologies provide a logical antecedent not only to geometric spaces, objects, and their transformations, but (I will argue) also to aesthetic situations that transform in space and (over) time. This work will focus on the latter spaces (or situations) as they present in the literary, visual, and performance arts to demonstrate how the contextualization that occurs in each functions as a diegetic mechanism and supports a homology between mathematical and literary disciplines.

For the purposes of this study, a preliminary definition of diegesis begins with acknowledging the diachronic motion of objects interacting, and consequently changing, within a well-defined space. However, it soon sheds this pedestrian conception in favor of one that explores transformations of the spaces themselves. Since each topology comprises a logical context that imposes behaviors and constraints on the elements that populate it, diegesis becomes that warping of these spaces which induces its elements to produce peculiar trajectories in response to environmental vagaries. Thus, on the one hand, diegesis describes the delineation of a mathematical (or scientific) theory as a (mere) instance of (or contingency within) an overarching formal structure. On the other, it describes the traversal of a plot as a peculiar response to the folding of space that constitutes a situation’s motion between its opening and closing states.

…

Interestingly, when I was an undergraduate English major (aeons ago!), I wrote a senior thesis on Henry James called “Interplay.” I argued that in his novels The Portrait of a Lady and Washington Square, plot acts as a mechanism for revealing character, while the characters in turn shaped the plots (situations) they inhabited. Clearly, without knowing it, I was already having inchoate topological ideas. I see that argument I made many years ago reflected in the above discussion of Beckett—just with fancier language.